LESPRIT Edith France

Mem Kossony in Costume, Royal Palace, Cambodia, 1866 - Khmers

New product

190,00 €

Artist: Édith France LESPRIT

Series: Khmer Dancers, Cambodia

Title: "Mem Kossony in Costume", Royal Palace, Cambodia

Medium: Photograph taken by Édith France Lesprit with a Yashica camera in 1966. Digitized by photographer Pascal Danot in 2011 and printed, pencil-numbered, and pencil-signed by Lesprit in a limited edition of 30 prints.

Signature: Signed on the mat

Limited Edition: 30 numbered copies, marked in pencil on the mat.

Dimensions: Photograph without mat: 30 x 30 cm (11.8 x 11.8 in)

Notes: Mounted under a white 40 x 40 cm mat, ready for framing. Certificate of authenticity included.

Description:

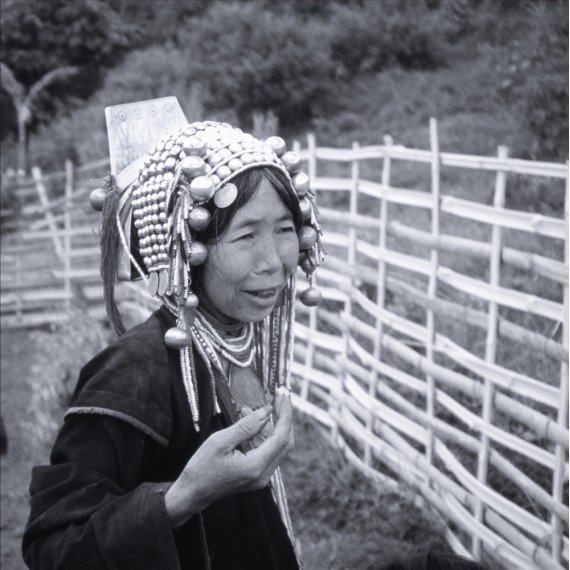

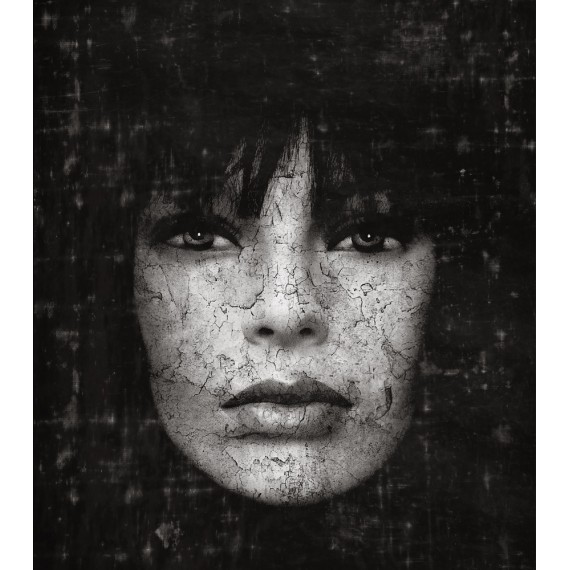

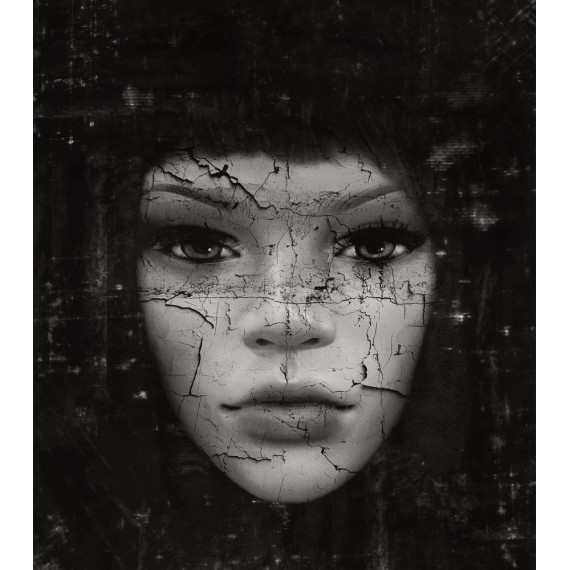

With “Mem Kossony in Costume”, Édith France Lesprit captures more than a portrait of a dancer — she captures an entire world, embodied in a gaze, a posture, a costume. Taken in 1966 inside the Royal Palace of Phnom Penh, this image is a suspended moment of grace, on the eve of a historical tragedy. It is a fragment of eternity, a gesture of remembrance from a time that has since vanished.

Mem Kossony, lead dancer of the second Khmer royal ballet, stands poised, adorned in a richly detailed costume: brocade fabric, ornate jewelry, and a traditional crown — sumptuous, yet never ostentatious. What Lesprit’s lens reveals is the rigor and purity of Khmer dance — a practice that blends discipline, sacred tradition, and cultural identity. Here, dance is not mere performance; it is devotion, transmission, and embodiment of heritage.

The tight framing, gentle lighting, and frontal composition lend the portrait a sense of quiet reverence. Mem Kossony appears both child and icon, human and mythological. In the smallest details — the precise extension of her fingers, the calm dignity of her stance — we see an art form shaped from early childhood by beauty and precision.

Seen in the light of Cambodia’s later history, this image carries a profound emotional weight. Most of the children visible in other photos from this series were killed during the Khmer Rouge regime. Lesprit could not have known that, in pressing the shutter, she was also preserving memory. Today, each photograph becomes a luminous tomb — a precious trace of what once was. Mem Kossony, who survived and later became a dance teacher, embodies a fragile resilience. Through her, the royal ballet was reborn — not as static folklore, but as an act of cultural resistance.

“Mem Kossony in Costume” is thus far more than an ethnographic or artistic document. It is an homage, a quiet form of reparation, a visual elegy offered to those who danced to preserve the soul of their people.

The Series: Khmer Dancers, Cambodia

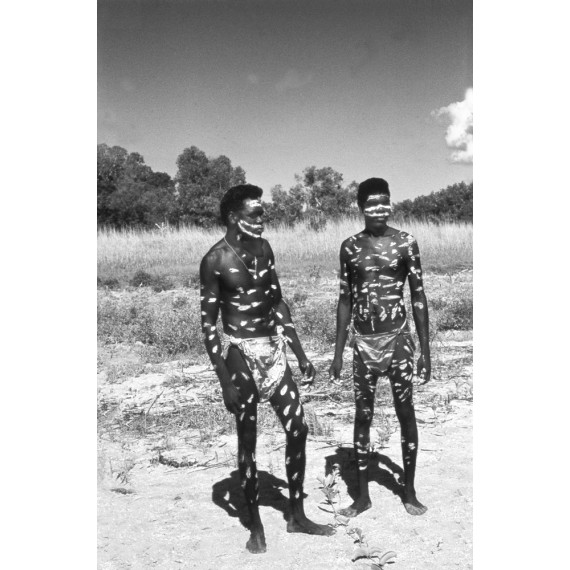

These photographs were taken in 1966 in Phnom Penh, inside the Royal Palace.

Thanks to a special permission from Her Majesty Queen Sisowath Kossamak (mother of Prince Norodom Sihanouk), I was allowed to attend and photograph ballet rehearsals in the Chamsaya Hall within the palace grounds. At the time, there were two “grand ballets,” including the renowned first ballet troupe that toured internationally—its star dancer was Her Royal Highness Princess Bopha Devi.

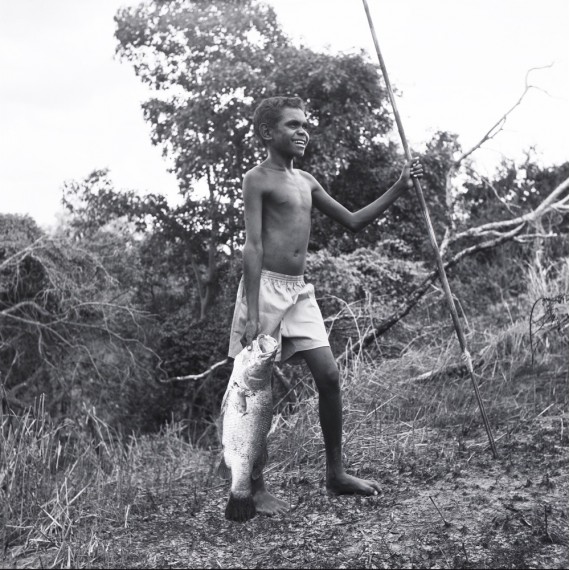

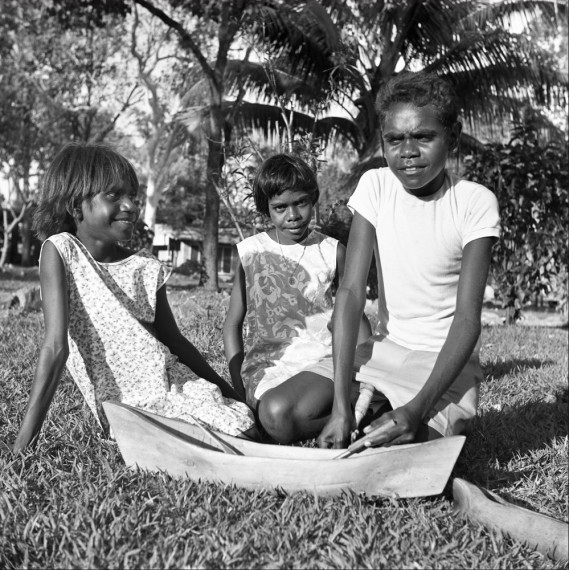

To be admitted to the dance school, young girls—often from rural villages—were selected by the first dance mistress and by Her Majesty the Queen.

All dancers lived in the palace under strict rules. Daily rehearsals, schooling, and annual dance exams determined their advancement to higher ranks.

The ballets mainly portrayed stories from the Ramayana legend—the lead roles of princes and princesses were always performed by girls. Boys played the antagonists: the Monkey King and his leaping warrior subjects.

There were around 300 dancers, musicians, and singers.

During the bloody Khmer Rouge period (1975–1979), about 90% of the royal ballet dancers, as well as musicians and singers, were exterminated. The magnificent costumes were burned, the jewels (tiaras, necklaces, gold and gemstone bracelets—rubies, sapphires, emeralds, diamonds) were stolen, all documents and photographs looted. Nothing remained—except about fifteen young dancers who suffered the tragic fate of becoming sex slaves to Khmer Rouge soldiers.

Thanks to Princess Bopha Devi, the royal Khmer ballet has risen from the ashes. From the moment the Site B Cambodian refugee camp (a FUNCINPEC camp) opened, Princess Bopha Devi began teaching little girls again.

I have a project to build a school of classical Khmer dance to train poor young girls, while also giving them education and moral values specific to Khmer dancers. The aim is to provide them with a dignified profession that protects them from serious dangers (prostitution, human trafficking, forced labor), and to help Cambodia reconnect with its past and extraordinary civilization—because Khmer dance is an essential part of Cambodian culture.

Mem Kossony – lead dancer of the second troupe – survived the massacres but was forced into sexual slavery. She is now a dance teacher for Bopha Devi’s ballet company. The other children visible in the photograph were killed.

— Édith France Lesprit

Biography:

Édith France Lesprit was born in Paris in 1937. She studied ethnology in the United Kingdom. In 1964, she left Britain for Asia. In 1965, she encountered the Iban tribe, with whom she lived for several months—this became the subject of her thesis. She later lived among several other Asian tribes, from whom she brought back valuable documentary photographs.

In 1967, she met Mother Teresa for the first time in Calcutta. She obtained her diplomas in traditional Chinese medicine in 1975. Between 1970 and 1980, she carried out many humanitarian missions with Mother Teresa’s missionaries in the Charité hospices in Tejgaon, Bangladesh, as well as with the Salesian Sisters.

In 1976, she published Enfer d'où je viens ("Hell Where I Come From"), an important testimony about Bangladesh, which won the Montyon Prize from the Académie française. In parallel, she wrote several novels for young readers, inspired by her encounters with tribes and her humanitarian work, under her own name and the pseudonym Éric Lestier.

In 1978, she won the Grand Prize at the 7th Azur Biennial for a book on Chinese medicine. In the 1980s, she worked extensively in Cambodian and Laotian refugee camps in Thailand and was invited to speak on the issue around the world.

From 1990 to 2010, she trained “barefoot doctors” in Ethiopia (local nurses providing basic healthcare). She also worked in leper colonies, bush dispensaries, orphanages, and homes for AIDS patients in Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. She has also led efforts to help disabled animals near Bangkok.

She published an autobiographical novel in 2009, The Kingdom of Forgotten Gods, recounting her journey with the Iban of Borneo.

Today, she continues her humanitarian work worldwide, especially through her project to build a school of classical Khmer dance in Cambodia.

"My project is to build a school of classical Khmer dance to train poor girls while giving them an education and moral values specific to Khmer dancers. The goal is to provide them with a dignified profession that steers them away from serious dangers (prostitution, human trafficking, forced labor), and to help Cambodia reconnect with its past and extraordinary civilization, since Khmer dance is a vital part of Cambodian culture."

Her photographs were exhibited in a gallery for the first time in 2011 at Galerie Roussard in the exhibition "Tribes."