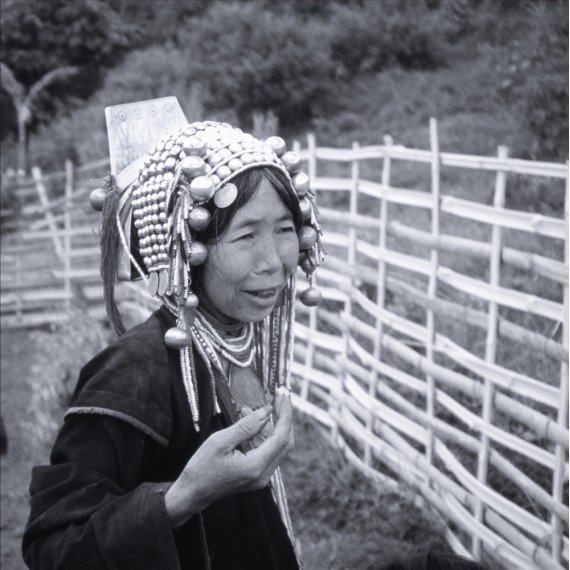

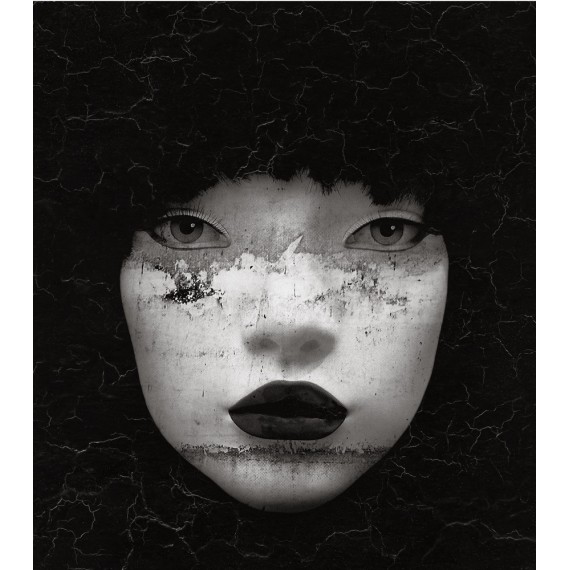

Artist: Édith France LESPRIT

Series: The Gubabingus, Australia

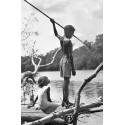

Title: “Spear Fishing” – The Gubabingus, Australia

Technique: Photograph taken by Édith France Lesprit using a Yashica camera in 1966. Digitized by photographer Pascal Danot in 2011 and printed, hand-numbered and hand-signed by Lesprit in a limited edition of 30 prints.

Signature: Signed on the matboard

Limited Edition: Limited to 30 copies, numbered in pencil on the matboard.

Dimensions: Dimensions of the photograph without matboard: 30 x 30 cm (11.8 x 11.8 inches)

Notes: Mounted under a white 40 x 40 cm matboard, ready for framing. Certificate of authenticity included.

Description:

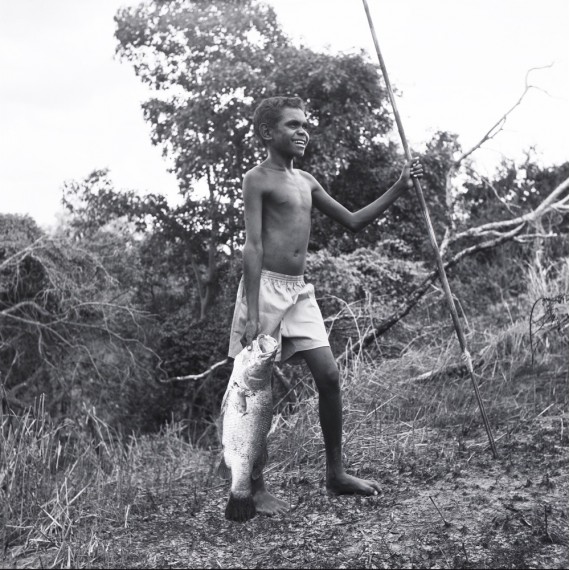

In “Spear Fishing”, Édith France Lesprit captures a moment of daily life that is both understated and symbolic. Two Aboriginal children stand on a fallen tree above a river, frozen in a silent moment of tension. The boy, standing with his spear raised, seems intent on proving something — not only his skill at fishing, but perhaps also his confidence in front of the girl seated nearby, calm and observant.

This seemingly simple image reveals a subtle dynamic: the desire to be seen, the need for recognition. The boy's almost heroic posture — leg stretched, arm lifted, eyes fixed — evokes traditional rites of passage into adulthood. Yet in this context, it also carries a more intimate, almost theatrical quality: a gesture of youthful bravado, a performance to impress.

True to her humanist approach, Lesprit imposes nothing. She allows the scene to unfold naturally, in ambient light, without interference. The black and white enhances the density of the textures: the rough bark, the creased clothing, the still water. Everything contributes to a carefully balanced composition. The diagonal lines of the branches and the spear structure the image with finesse, creating a visual rhythm that amplifies the scene’s internal tension.

Beneath the surface, the photograph also speaks to a vanished world — a way of life grounded in ancestral knowledge, early autonomy, and quiet social bonds. “Spear Fishing” captures a fragment of this reality — and beyond ethnographic value, it reveals the universality of a gesture: the longing to be noticed, admired, recognized. Perhaps even loved.

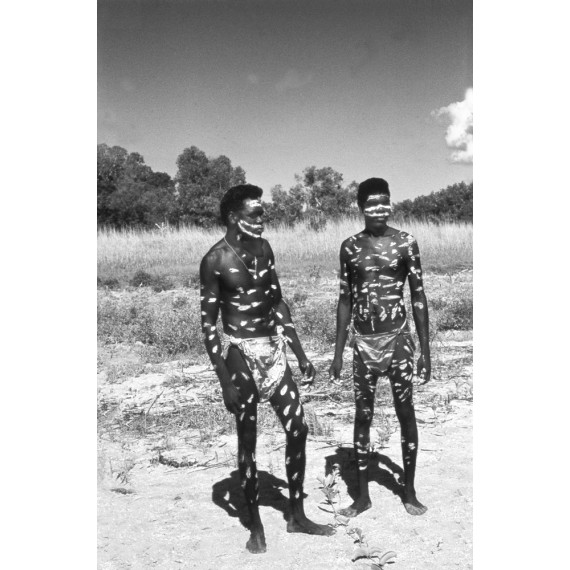

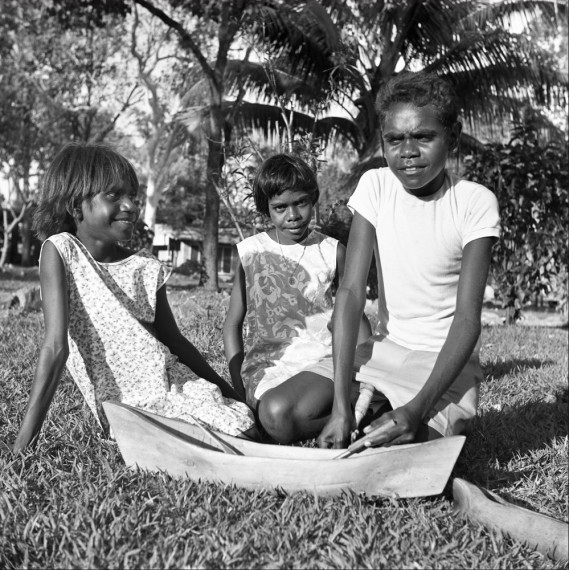

The Series: The Gubabingus, Australia

The Gubabingus arrived on Australian land approximately 40,000 years ago, likely accompanied by their dogs — the now-famous dingoes — during the prehistoric period when the Australian continent was still connected to New Guinea via the Cape York Peninsula.

They are among the last survivors of Lower Paleolithic culture, predating the Stone Age. They practiced no agriculture or animal husbandry, living solely by hunting, fishing, and gathering. They had neither dwellings nor clothing and moved constantly across the desert from one waterhole to another. Each clan had totems that guarded their territory and sacred water sources.

Among their customs were the abandonment of the elderly and the execution of one child in the case of twins to limit population growth.

Men and women lived separately. From the age of ten, young boys had to survive alone in the desert for two months. If they returned, a rite of passage initiated them into adulthood, and they joined the hunters.

The first settlers arrived in Australia in 1770. Soon followed massacres of Aboriginal people and waves of deadly Western diseases.

From 1909 to 1969, under the “White Australia” policy, Aboriginal children of mixed European descent were taken from their mothers and placed in institutions to be raised and assimilated into white culture.

Until the 1930s, thousands of Aboriginal people were interned and placed in reserves managed by white authorities. Sports, entertainment, and military service were the few available avenues for acceptance. During World War II, many Aboriginal men joined the armed forces.

In the 1950s, the Australian government implemented a policy of assimilation aimed at gradually integrating Aboriginal people into Western ways of life.

Since 1976, a partial restitution of land to Aboriginal communities has been underway. Many have returned to their ancestral homelands, now living in so-called "communities," though many of these groups suffer from alcoholism and cultural loss. The way of life Lesprit was still able to photograph in 1966 has since disappeared.

Lieutenant James Cook wrote in 1770 about the Aboriginal peoples:

“In reality they are far happier than we Europeans... They live in tranquility undisturbed by inequality of condition. The land and sea provide them with all they need to live... They dwell in a pleasant climate and breathe pure air... They do not strive for abundance.”

Biography:

Édith France Lesprit was born in Paris in 1937. She studied ethnology in Great Britain. In 1964, she left the UK for Asia. In 1965, she encountered the Iban tribe, with whom she lived for several months — an experience that became the subject of her academic thesis.

She would go on to live with various Asian tribes, documenting their lives through profoundly important photographs. In 1967, she met Mother Teresa in Calcutta for the first time. She earned her diploma in Traditional Chinese Medicine in 1975.

Between 1970 and 1980, she carried out numerous humanitarian missions with Mother Teresa’s missionaries at the Charité hospices in Tejgaon, Bangladesh, and with the Salesian Sisters.

In 1976, she published Enfer d'où je viens (Hell I Come From), a powerful account of Bangladesh that received the Montyon Prize from the Académie française.

She has also written several novels for young adults inspired by the tribes she encountered or her humanitarian work — some under the pseudonym Éric Lestier, others under her own name.

In 1978, she won the Grand Prize at the 7th Azur Biennale for a book on Chinese medicine.

In the 1980s, she carried out extensive humanitarian work in Cambodian and Laotian refugee camps in Thailand, speaking about the crisis around the world.

From 1990 to 2010, she trained “barefoot doctors” in Ethiopia — local nurses capable of providing basic medical care. She also worked in leper colonies, rural clinics, orphanages, and shelters for AIDS patients in Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

She led several initiatives to support disabled animals near Bangkok and published an autobiographical novel, Le royaume des Dieux oubliés (The Kingdom of Forgotten Gods), in 2009, recounting her journey with the Iban of Borneo.

Today, she continues her humanitarian work worldwide, notably through the creation of a classical Khmer dance school in Cambodia.

“My project is to build a classical Khmer dance school to train underprivileged girls while giving them an education and the moral values specific to Khmer dancers. The goal is to provide them with a dignified profession, protecting them from dangers such as prostitution, human trafficking, and forced labor, while also helping Cambodia reconnect with its past and its extraordinary civilization, as classical dance is an essential part of Khmer culture.”

Her photographs were exhibited for the first time in a gallery in 2011 at the Roussard Gallery, in the Tribes exhibition.