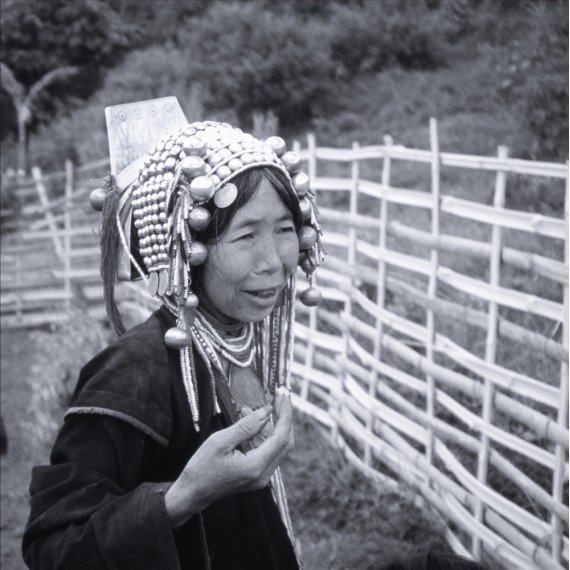

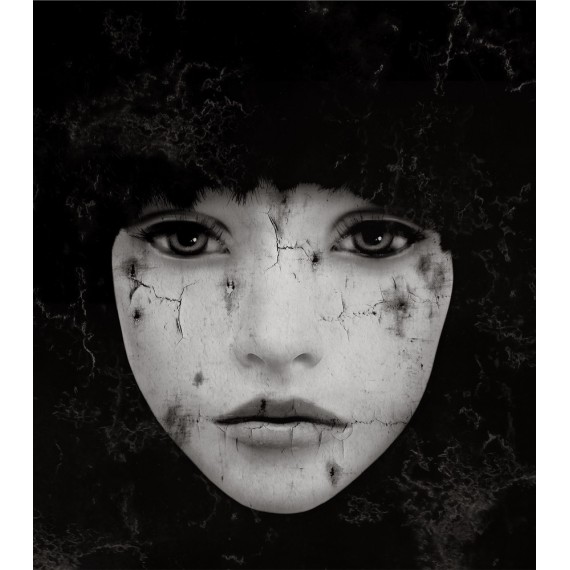

Artist: Édith France LESPRIT

Series: The Akhas, Laos

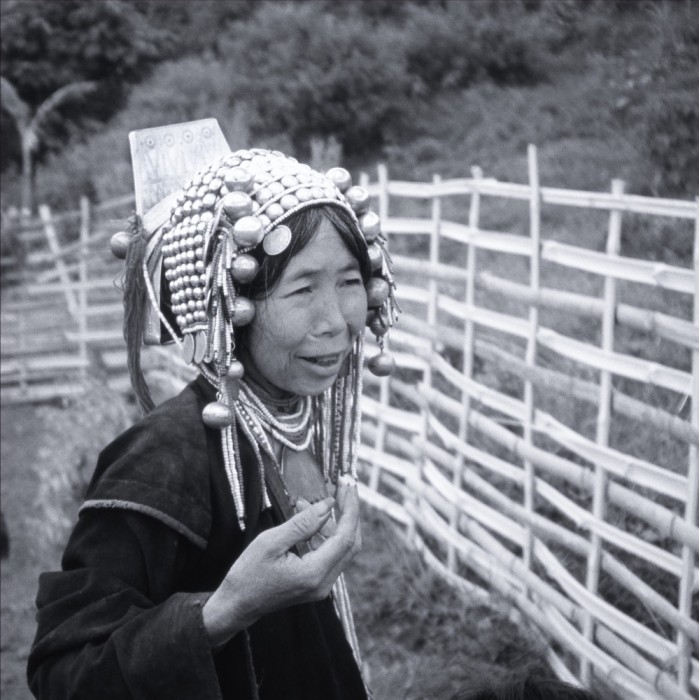

Title: " Akha Woman " – The Akhas, Laos

Technique: Photograph taken by Édith France Lesprit with a Yashica camera in 1966. Digitized by photographer Pascal Danot in 2011 and printed, hand-numbered and signed in pencil by Lesprit in a limited edition of 30 prints.

Signature: Signed on the mat

Limited Edition: Edition limited to 30 copies, numbered in pencil on the mat.

Dimensions: Photo dimensions without mat: 30 x 30 cm (11.8 x 11.8 inches)

Notes: The photograph is mounted under a white mat (40 x 40 cm), ready for framing. Certificate of authenticity included.

Description:

This black-and-white photograph captures an Akha woman in a moment of everyday life, filled with authenticity and quiet dignity. Her gaze, turned slightly off-frame, and the expression on her face suggest a spontaneous gesture or a passing conversation. This gives the image a vivid quality, far from staged or static portraits.

The elaborate headdress — adorned with beads, coins, and metallic elements — immediately draws the viewer’s attention. It contrasts with the simplicity of her dark clothing, creating a strong visual balance. Each detail of the headdress speaks of heritage, social status, and cultural identity. The photographer highlights these features without artifice, through tight framing and the use of natural light.

In the background, a bamboo fence stretches into the distance, guiding the eye and setting the scene in a rural, mountainous landscape. Its rhythmic repetition adds structure to the composition without distracting from the subject.

As always, Édith France Lesprit adopts a humanistic and respectful approach. She avoids exoticism or dramatization, choosing instead to capture presence, texture, and authenticity. This photograph does not simply document a culture — it reveals a person, in her posture, her context, and her living memory.

The Series – The Akhas, Laos:

Of Tibeto-Burmese origin, the Akhas live in mountainous regions at over 1,200 meters above sea level. Their huts are built directly on the ground, facing the rising sun, and made of bamboo, thatch, or fan palm leaves. Cautious of outsiders—especially those from lower altitudes, whom they believe bring harmful spirits—they are animists by belief.

They cultivate opium, though they are minimal consumers themselves, selling nearly all of it. This trade is one of the few reasons they allow visitors, as they rarely leave their villages, even for commerce. Their livelihood is based on livestock, and dog meat is part of their diet.

Virgin girls are deflowered by the aw shaw, the official male of the village or village cluster, during a religious ceremony. A man may have several wives, and young girls can be sold as slaves. Women, along with children, do all the work—both in the fields and at home—while men smoke and talk.

Akha men shave their heads, keeping a small braid, which they believe is vital to their sanity. Severe punishments differ by gender: a woman may be stoned to death, while the equivalent male punishment is to cut off his braid, which can drive him insane.

Lesprit met the Akhas in Laos, though their communities also extend into China and Thailand, where land seizures by authorities have been frequent. In Laos, they inhabit remote, hard-to-access mountains and live between tradition and modernity. Much of their culture remains intact, and they sometimes welcome tourists. One visitor noted seeing soda can fragments sparkling among the decorations on the women's headdresses. The same traveler reported that Akha men are now "more oriented toward the civilized world of the lowlands."

From a travel website:

"What a surprise to learn that the night before, half the village had gathered in the chief’s house to watch a German film dubbed in Thai, followed by a Lao karaoke DVD! It seems incredible for a village without electricity. Everyone contributes to acquiring the necessary equipment."

Biography:

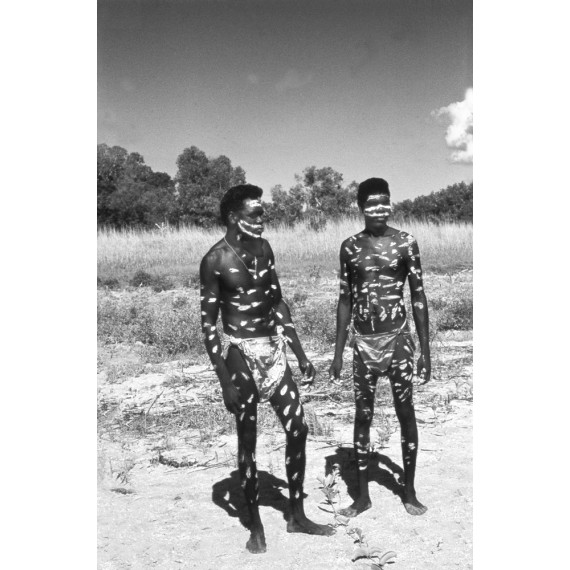

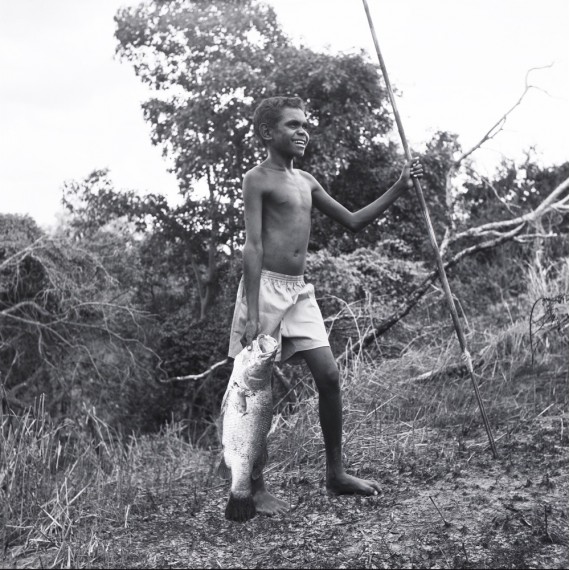

Édith France Lesprit was born in Paris in 1937. She studied ethnology in the United Kingdom. In 1964, she left for Asia. In 1965, she encountered the Iban tribe, with whom she lived for several months—a subject that became the basis of her thesis.

She later lived among several Asian tribes, documenting their lives through significant photographic work. In 1967, she met Mother Teresa in Calcutta. In 1975, she earned a degree in traditional Chinese medicine.

Between 1970 and 1980, she led many humanitarian missions with Mother Teresa’s missionaries in charity hospices in Tejgaon, Bangladesh, as well as with the Salesian Sisters. In 1976, she published Hell Where I Come From, a key testimony about Bangladesh, which won the Montyon Prize from the Académie Française.

In parallel, she wrote several young adult novels inspired by the tribes she encountered or her humanitarian work—some under the pseudonym Éric Lestier, others under her own name. In 1978, she received the Grand Prize at the 7th Azur Biennial for a book on Chinese medicine.

In the 1980s, she conducted humanitarian work in Cambodian and Laotian refugee camps in Thailand, sharing her insights worldwide. From 1990 to 2010, she trained "barefoot doctors" (locally trained nurses) in Ethiopia. She also supported leper colonies, bush clinics, orphanages, and AIDS care centers in Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Additionally, she engaged in rescue efforts for disabled animals near Bangkok.

She published an autobiographical novel in 2009, The Kingdom of Forgotten Gods, recounting her journey with the Iban of Borneo.

Today, she continues her humanitarian efforts worldwide, notably through the construction of a Khmer classical dance school in Cambodia:

“My project is to build a Khmer classical dance school for underprivileged girls, while also giving them an education and moral values linked to this tradition. The goal is to provide a dignified profession, which can help protect them from dangers such as prostitution, human trafficking, and forced labor. At the same time, it helps Cambodia reconnect with its past and cultural heritage, as Khmer dance is an essential part of its identity.”

She first exhibited her photographs in a gallery in 2011, at Galerie Roussard, during the "Tribes" exhibition.