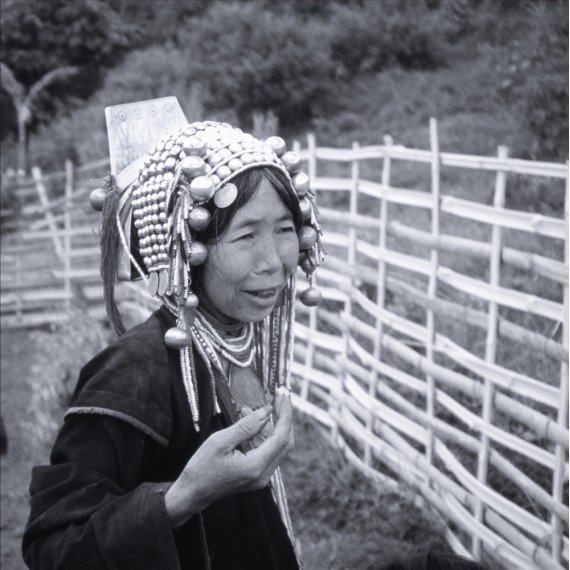

Artist: Édith France LESPRIT

Series: The Gubabingus, Australia

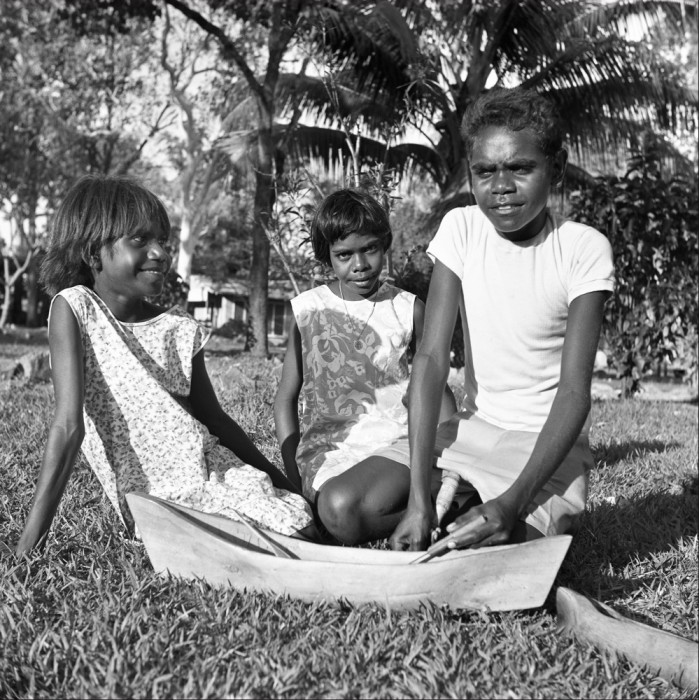

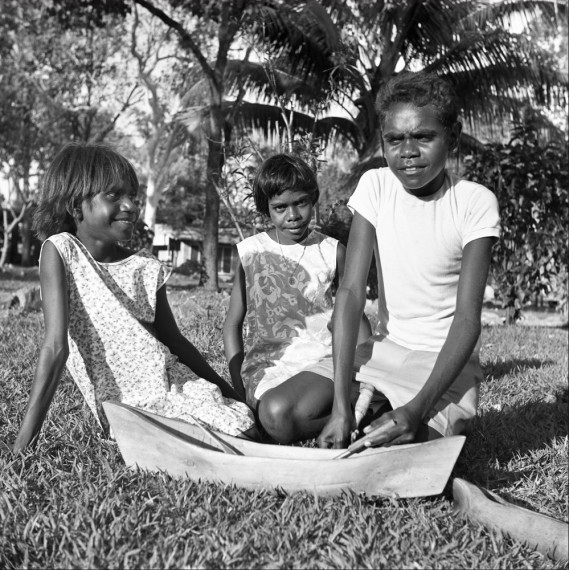

Title: “Gunmay, Multara and Kindu” – The Gubabingus, Australia

Technique: Photograph taken by Édith France Lesprit with a Yashica camera in 1966. Digitized by photographer Pascal Danot in 2011 and printed, hand-numbered and hand-signed by Lesprit in a limited edition of 30 prints.

Signature: Signed on the matboard

Limited Edition: Limited edition of 30 copies, numbered in pencil on the matboard.

Dimensions: Dimensions of the photo without matboard: 30 x 30 cm (11.8 x 11.8 inches)

Notes: The photo is mounted under a white 40 x 40 cm matboard, ready for framing. Comes with a certificate of authenticity.

Description:

In “Gunmay, Multara and Kindu”, Édith France Lesprit offers a photograph of rare gentleness, both documentary and deeply human. Taken in 1966 with a Yashica camera, the black-and-white image shows three Aboriginal children sitting in the grass under palm trees, bathed in natural light. This suspended moment, imbued with simplicity, reflects a gaze of attentiveness and respect.

The composition is built around a visual triangle formed by the children's positions and crossed gazes. Their varied expressions—laughter, seriousness, attentiveness—breathe life into the image with a nearly spontaneous dynamic. There's a clear refusal of the posed shot in favor of capturing a genuine, shared moment.

The black-and-white treatment avoids the picturesque: it emphasizes contrast, texture, and light, particularly the fabrics of the dresses, the children's skin, and the lush vegetation in the background. This choice shifts the viewer’s focus back to the human presence and the moment itself, rather than toward any exoticizing effect.

Through this image, Lesprit documents a reality already under threat at the time. The series The Gubabingus, Australia carries this quiet urgency: the need to bear witness to an ancestral way of life on the verge of vanishing. This photograph, both modest and rich, does not merely depict a culture—it makes it tangible, embodied by these children in their everyday life, without artifice.

Édith France Lesprit brings, as throughout her work, a deeply humanist gaze. She observes without intruding, captures without transforming. The photographic act becomes one of quiet listening, where the precision of the framing and the simplicity of the scene reveal a fundamental truth.

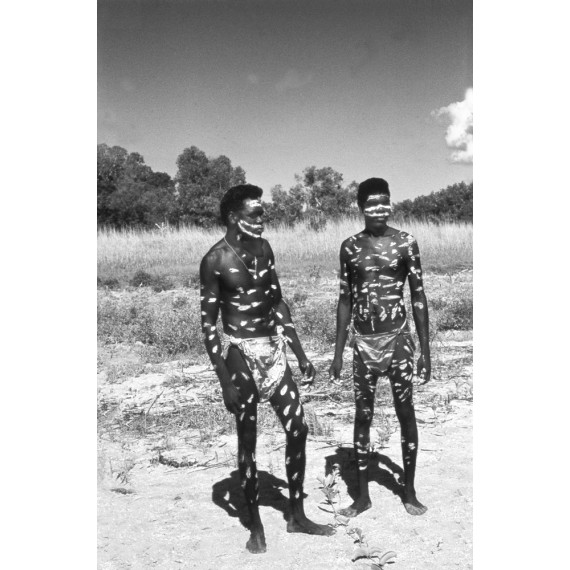

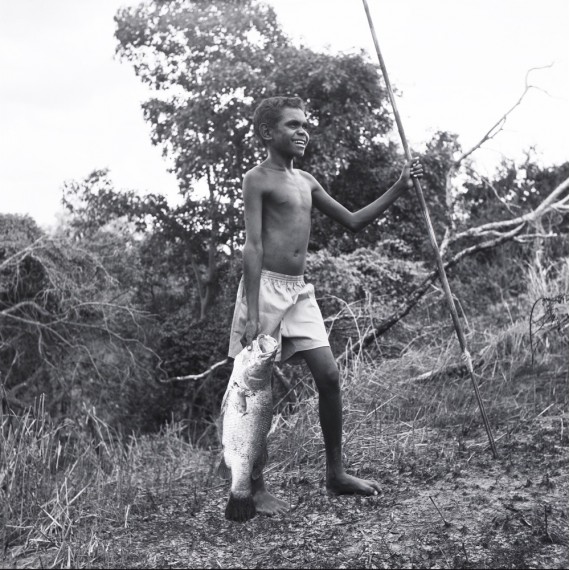

The Series: The Gubabingus, Australia

The Gubabingus arrived on Australian land around 40,000 years ago, likely with their dogs—the now-famous dingoes—during prehistoric times, when the Australian continent was still connected to New Guinea via the Cape York Peninsula.

They are among the last surviving groups from the Lower Paleolithic culture, predating the Stone Age. They practiced neither agriculture nor animal husbandry, living instead from hunting, fishing, and gathering. They had no fixed dwellings or clothing and wandered the desert from one water source to another. Each clan possessed totems guarding their territory and sacred water points.

Among their customs were the abandonment of the elderly and the execution of one twin in cases of multiple births, as a means of population control.

Men and women lived separately. From the age of ten, young boys had to survive alone in the desert for two months. If they passed this test of courage and endurance and returned to the camp, a ceremony would initiate them, and they would join the hunters.

The first settlers arrived in Australia in 1770. Soon after came massacres and the spread of Western diseases that decimated Aboriginal populations.

From 1909 to 1969, the policy of "White Australia" was in place: Aboriginal children of mixed European descent were taken from their mothers and placed in institutions to be raised and assimilated into white society.

Until the 1930s, thousands of Aboriginal people were interned and placed in reserves managed by white officials. Sport, entertainment, and military service were among the few ways they could gain acceptance. During World War II, many Aboriginal men enlisted in the armed forces.

In the 1950s, the government adopted an assimilation policy aimed at aligning Aboriginal life with that of other Australians.

Since 1976, land has been partially restored to Aboriginal communities. Many have returned to ancestral lands—homelands—now living in reserves known as “communities.” Unfortunately, these groups have faced the ravages of alcohol and cultural disintegration. The way of life that Lesprit was still able to photograph in 1966 no longer exists.

Lieutenant James Cook wrote in 1770 about the Aboriginal peoples: “They are in reality far more happy than we Europeans… They live in tranquility, undisturbed by inequality of condition. The Earth and the sea provide them with all necessary things to live… They live in a mild climate and have very healthy air… they do not seek abundance.”

Biography:

Édith France Lesprit was born in Paris in 1937. She studied ethnology in Great Britain. In 1964, she left Britain for Asia. In 1965, she encountered the Iban tribe, with whom she lived for several months—an experience that became the subject of her thesis.

She later lived among several Asian tribes, from which she brought back significant documentary photographs. In 1967, she had her first meeting with Mother Teresa in Calcutta. She earned her degree in Traditional Chinese Medicine in 1975.

Between 1970 and 1980, she carried out numerous humanitarian missions with the missionaries of Mother Teresa in the hospices of Charity in Tejgaon, Bangladesh, and with the Salesian Sisters.

In 1976, she published Enfer d’où je viens (Hell I Come From), a powerful testimony on Bangladesh, which received the Montyon Prize from the Académie Française.

She also authored several novels for young readers inspired by the tribes she encountered or her humanitarian work—some under the pseudonym Éric Lestier, others under her real name.

In 1978, she was awarded the Grand Prize at the 7th Azur Biennale for a book on Chinese medicine.

In the 1980s, she led humanitarian missions in Cambodian and Laotian refugee camps in Thailand and was invited to speak about these issues around the world.

From 1990 to 2010, she trained “barefoot doctors” in Ethiopia—local nurses trained to provide basic care. She also worked in leper colonies, bush clinics, orphanages, and shelters for AIDS patients in Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam.

She led initiatives to help disabled animals near Bangkok and published an autobiographical novel, Le royaume des Dieux oubliés (The Kingdom of Forgotten Gods), in 2009, recounting her journey with the Iban of Borneo.

Today, she continues her humanitarian work worldwide, including building a classical Khmer dance school in Cambodia.

“My project is to build a classical Khmer dance school to train poor girls while giving them an education and moral values specific to Khmer dancers. The aim of this training is to give them a respectable profession, shielding them from serious dangers (prostitution, human trafficking, labor exploitation), and also to help Cambodia reconnect with its past and extraordinary civilization, since classical dance is an essential part of Khmer culture.”

Her photographs were exhibited in a gallery for the first time in 2011 at the Roussard Gallery in the exhibition Tribes.