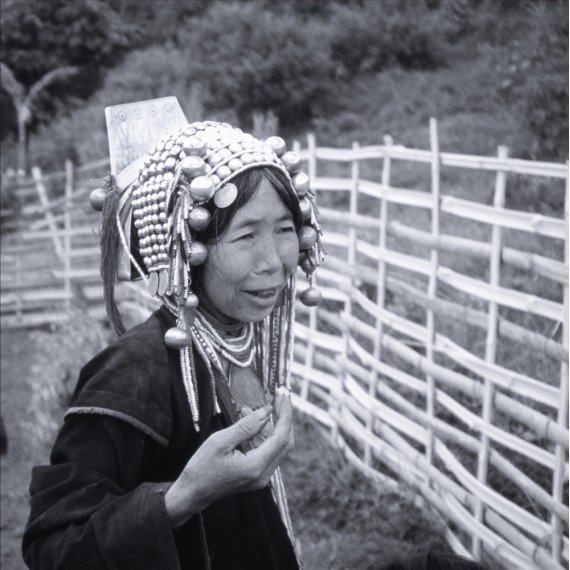

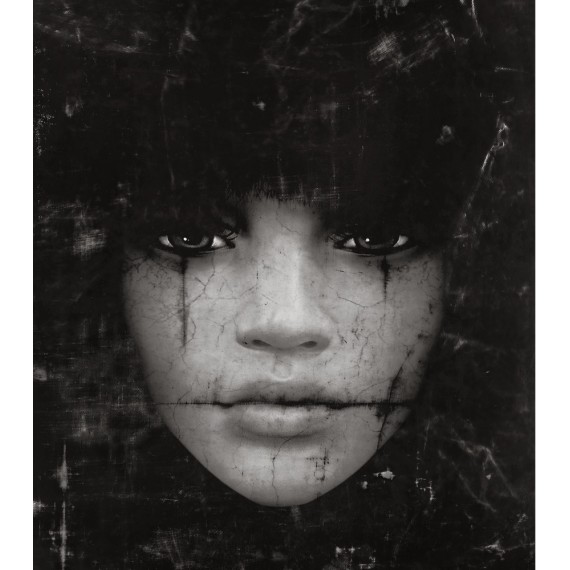

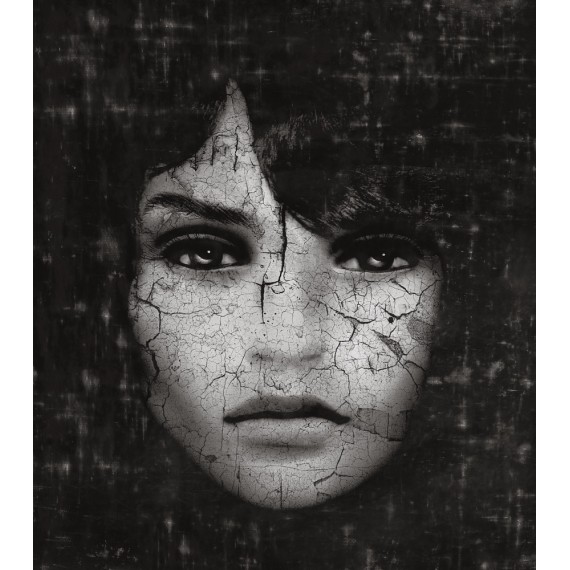

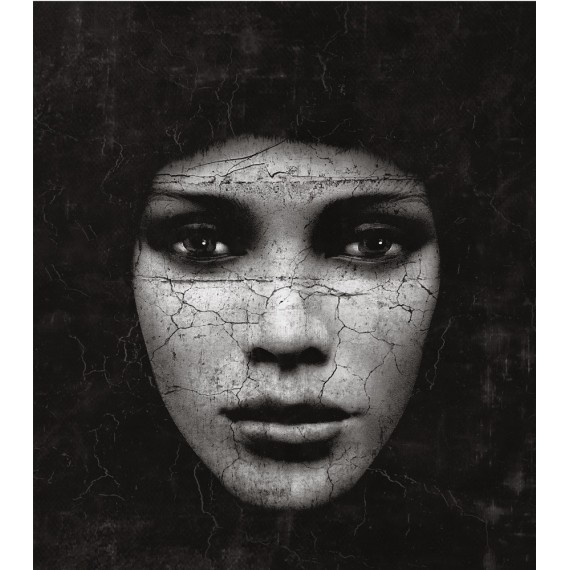

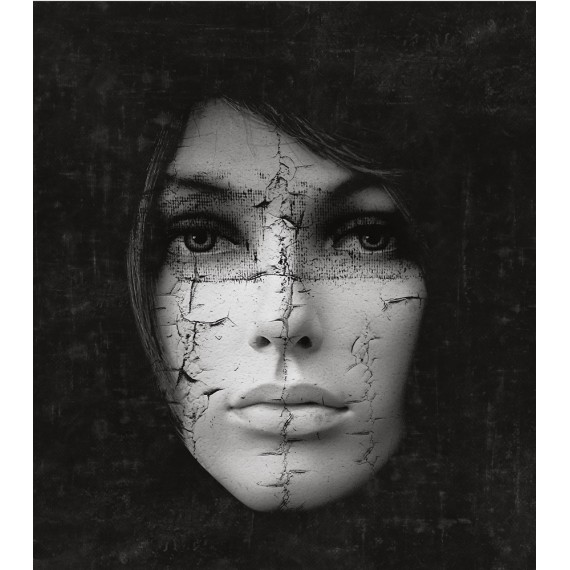

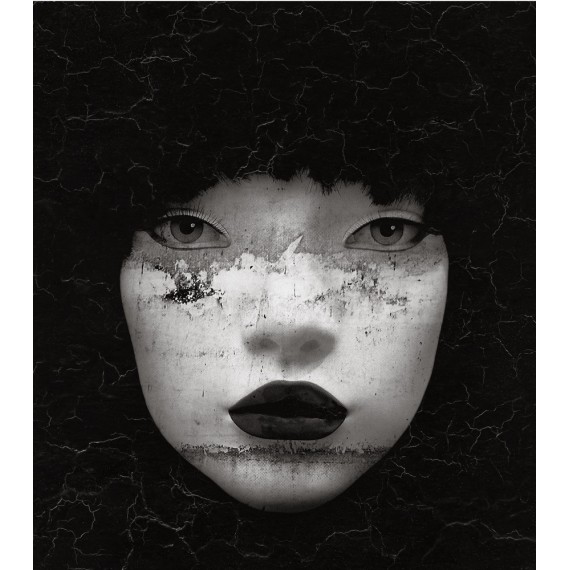

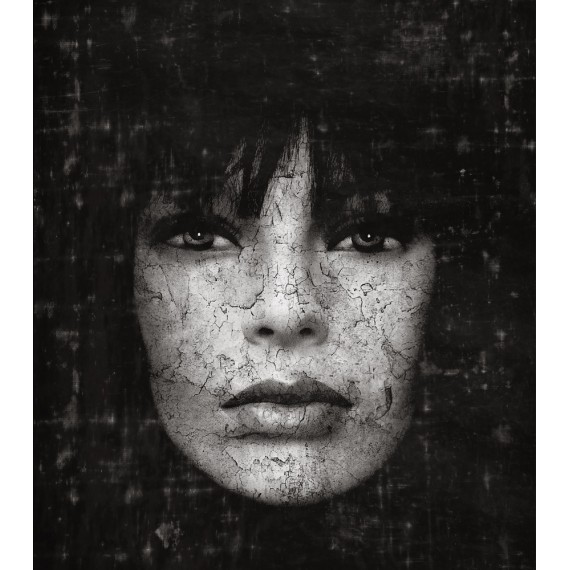

Artist: Édith France LESPRIT

Series: The Ibans, Borneo

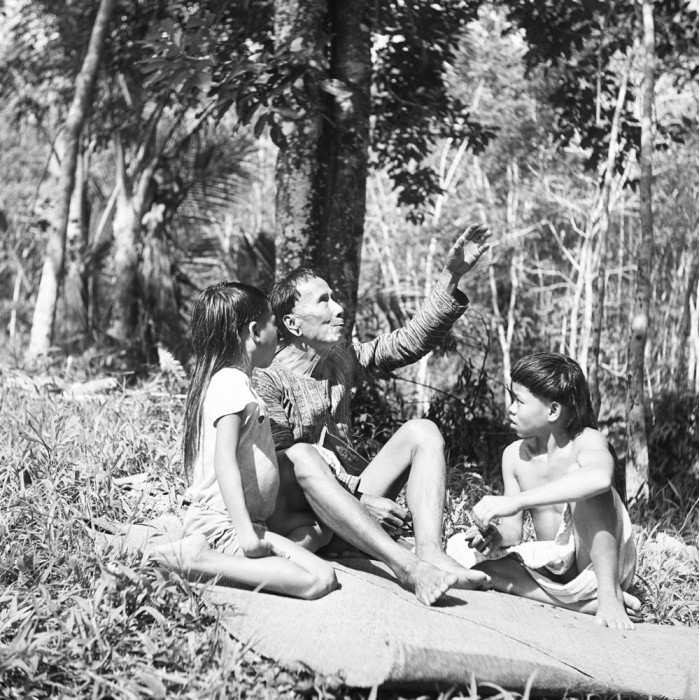

Title: The Legend of the Hornbill – Ibans, Borneo, 1965

Medium: Photograph taken by Édith France Lesprit with a Yashica camera in 1965. Digitized by photographer Pascal Danot in 2011, printed, pencil-numbered, and pencil-signed by Lesprit in a limited edition of 30 prints.

Signature: Signed on the mat

Limited Edition: 30 copies, numbered in pencil on the mat

Dimensions: Photo size without mat: 30 x 30 cm (11.8 x 11.8 in)

Notes: Mounted under a white 40 x 40 cm mat, ready to be framed. Certificate of authenticity included.

Description:

In The Legend of the Hornbill, Édith France Lesprit captures both the moment and the eternal. Taken in 1965 deep in the jungle of Sarawak, this photograph immerses us in the daily life of the Iban people—a community of hunters, warriors, and poets—living in close harmony with nature and the invisible world.

The hornbill, a sacred bird with mythological traits, holds a central place in the animist beliefs of the Iban. It is both a messenger of the spirits and a symbol of the connection between realms. Through her Yashica lens, Lesprit does more than document: she interprets—with modesty and precision—a vision of the world that is vanishing.

The composition of the image, direct and organic, evokes respect, quiet presence, and a sense of wonder before a forgotten cosmogony. This photograph is not just a record—it bears the trace of an ethnographic gaze imbued with sensitivity, the kind of closeness that only deep immersion can yield. Lesprit lived for several months among the Ibans, sharing in their rituals, their dances, and their stories—including that of the hornbill.

Today, 95% of Borneo’s primary rainforest has been destroyed. With it, this free and sacred way of life has all but disappeared. Most of the tribes that once inhabited it now survive only through tourism, emptied of their essence. This photograph offers a fragment of their soul: it makes the invisible visible.

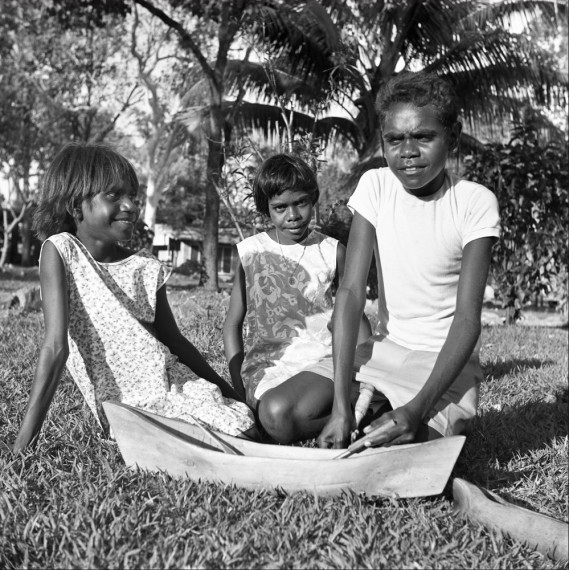

Through this series, Lesprit is not merely preserving images; she is asserting memory, presence, and dignity. The Legend of the Hornbill reminds us that every lost culture is a wound to humanity—and that sometimes, art is the delicate mourning we have left.

The Series: The Ibans, Borneo

The Ibans live communally in longhouses—raised wooden structures built along rivers. As animists, they believe in an invisible world populated by good and evil spirits. Their sacred bird is the hornbill.

They practice strict monogamy—adultery is severely punished—though sexual freedom is accepted before marriage, even allowing for trial unions. Homosexuality is considered normal among the Ibans.

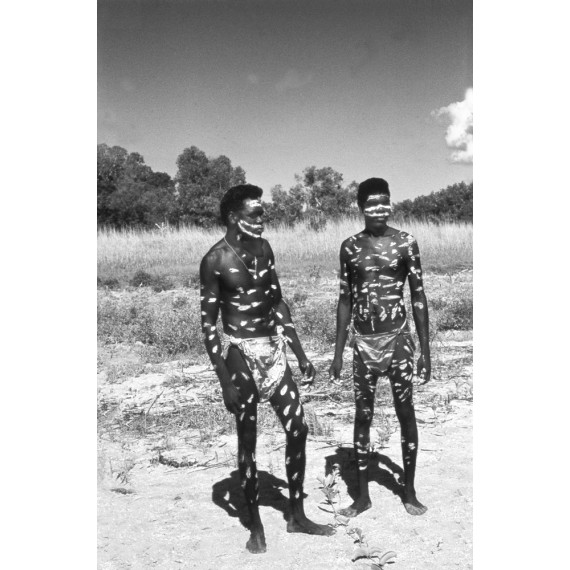

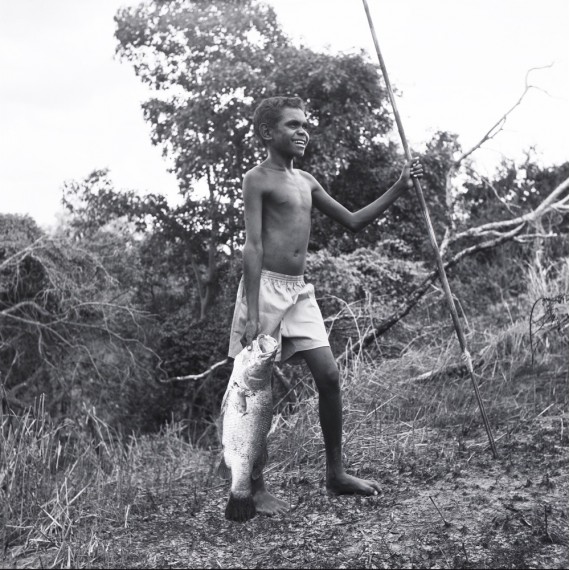

They are expert hunters, using blowpipes and sharpened wooden darts tipped with poison. They were also formidable warriors, known for headhunting—the skulls of enemies were hung at the entrance of their homes. For each head taken, a tattoo was added to a finger joint. The more joints tattooed, the more respected the man.

This practice has been outlawed by the Malaysian government for many years.

The Ibans once lived in the Sarawak region, in a dense, rich jungle teeming with plant and animal life. Today, 95% of that primary forest has been cleared and replaced by logging operations and palm oil plantations. The tribes who lived there have mostly disappeared.

Today, some Iban communities are exploited for tourism (longhouse visits, traditional dances, and costumes) so that passing “adventurers” can take photographs. Of course, the true Iban way of life—like that of many indigenous peoples worldwide—was one of freedom and harmony with the natural world. Sadly, that world is gone.

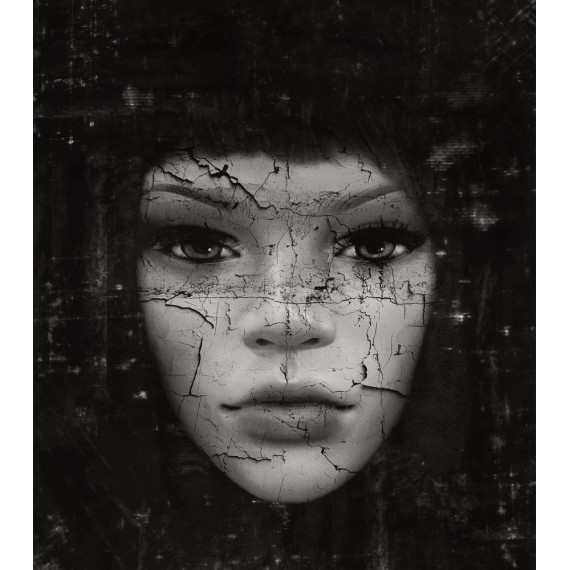

Biography:

Édith France Lesprit was born in Paris in 1937. She studied ethnology in the United Kingdom. In 1964, she left Britain for Asia. In 1965, she encountered the Iban tribe, with whom she lived for several months. This experience became the subject of her thesis. She later lived among several other Asian tribes, returning with invaluable documentary photographs.

In 1967, she met Mother Teresa for the first time in Calcutta. In 1975, she obtained her diploma in traditional Chinese medicine. From 1970 to 1980, she carried out numerous humanitarian missions with Mother Teresa’s missionaries in the Charité hospices in Tejgaon, Bangladesh, as well as with the Salesian Sisters.

In 1976, she published Enfer d’où je viens ("Hell Where I Come From"), an important testimony about Bangladesh that received the Montyon Prize from the Académie française. In parallel, she wrote several novels for adolescents inspired by the tribes she met or her humanitarian work—some under the pseudonym Éric Lestier, others under her own name.

In 1978, she won the Grand Prize at the 7th Azur Biennial for a book on Chinese medicine. In the 1980s, she worked extensively in Cambodian and Laotian refugee camps in Thailand and was invited to speak globally on the issue.

From 1990 to 2010, she trained "barefoot doctors" in Ethiopia (local nurses providing basic care). She also worked in leper colonies, bush dispensaries, orphanages, and AIDS care homes in Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Additionally, she led several projects to help disabled animals near Bangkok.

In 2009, she published The Kingdom of Forgotten Gods, an autobiographical novel recounting her journey with the Iban of Borneo.

Today, she continues her humanitarian efforts worldwide, notably through a project to build a school of classical Khmer dance in Cambodia:

"My project is to build a school of classical Khmer dance to train poor girls, while also offering them education and the moral values specific to Khmer dancers. The goal is to provide them with a dignified profession, one that protects them from serious dangers (prostitution, human trafficking, forced labor), and also to help Cambodia reconnect with its past and extraordinary civilization—since Khmer dance is an essential part of Cambodian culture."

Her photographs were exhibited in a gallery for the first time in 2011, at Galerie Roussard, in the exhibition "Tribes."