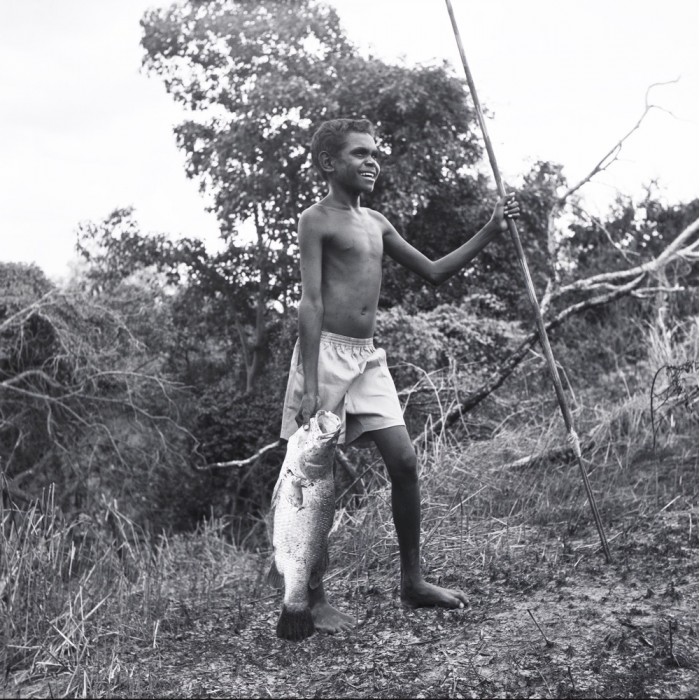

Artist: Édith France LESPRIT

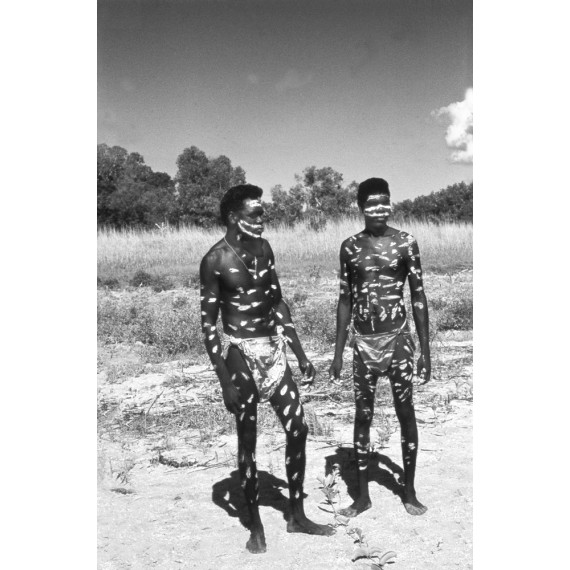

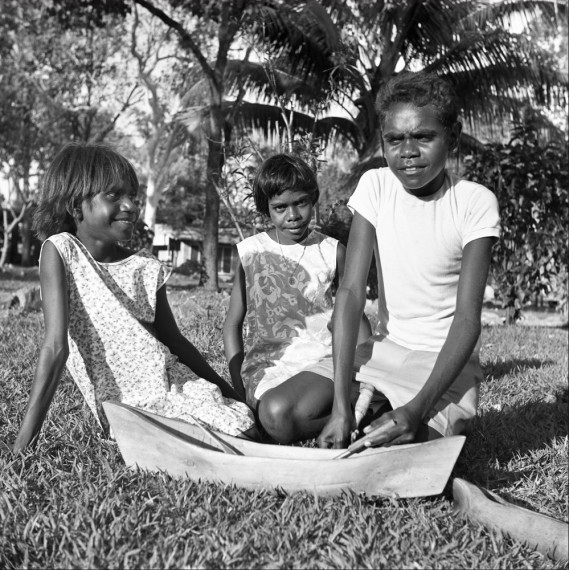

Series: The Gubabingus, Australia

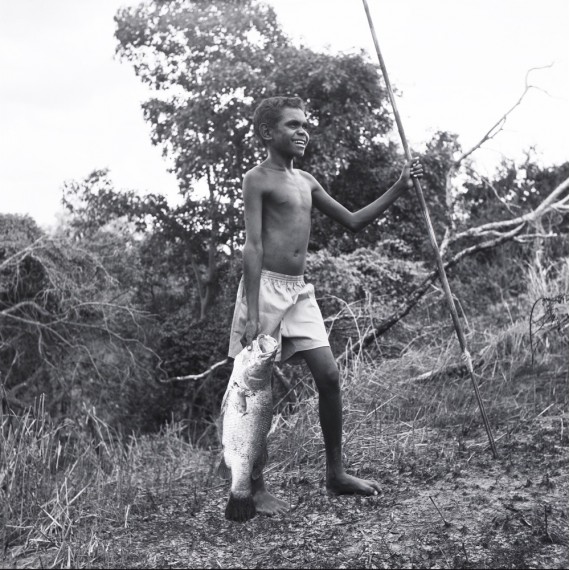

Title: Return from Fishing – The Gubabingus, Australia, 1966

Medium: Photograph taken by Édith France Lesprit with a Yashica camera in 1966. Digitized by photographer Pascal Danot in 2011 and printed, pencil-numbered, and pencil-signed by Lesprit in a limited edition of 30 prints.

Signature: Signed on the mat

Limited Edition: 30 numbered copies, marked in pencil on the mat

Dimensions: Photo size without mat: 30 x 30 cm (11.8 x 11.8 in)

Notes: Mounted under a white 40 x 40 cm mat, ready to be framed. Certificate of authenticity included.

Description:

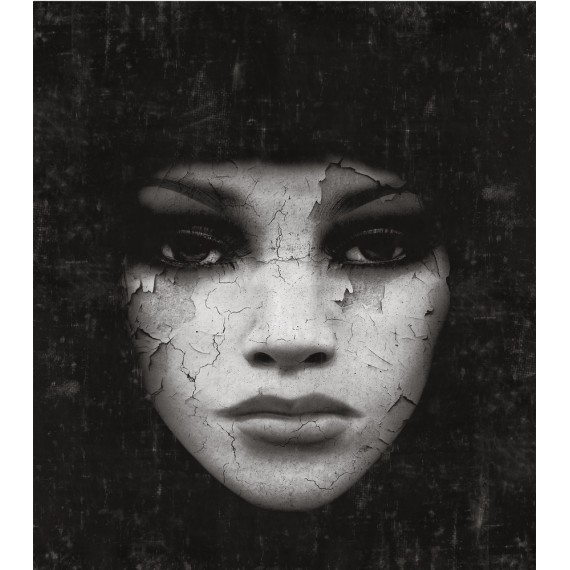

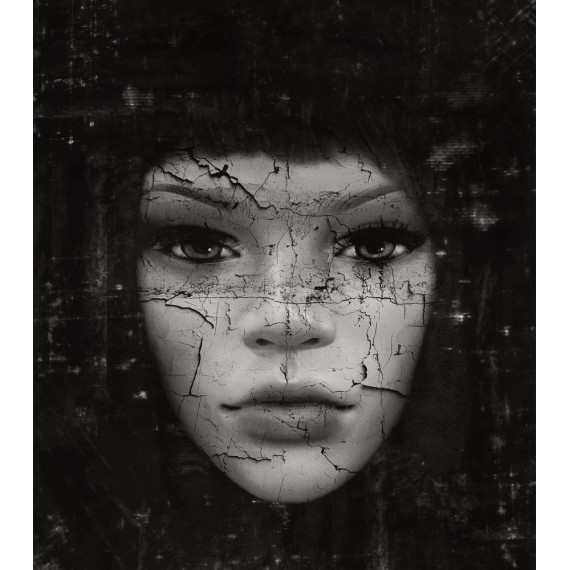

In Return from Fishing, Édith France Lesprit offers a portrait of an ancestral world in balance with nature. A young boy stands upright, holding a spear in one hand and a freshly caught fish in the other—embodying the quiet dignity of the last heirs to a millennia-old culture: that of the Gubabingus, an Aboriginal people of Australia.

The composition is pared-down, almost silent. The boy's gaze, directed toward the horizon, speaks as much of pride as of an uncertain future. His youthful body, already marked by effort and responsibility, evokes the rite of passage imposed on young boys from the age of ten—surviving alone in the desert for two months before being initiated into the community of hunters.

Shot in black and white, the photograph emphasizes the raw simplicity of the moment. There are no props, no theatrical staging—only earth, nature, the child, and the trace of his action. It is within this restraint that Lesprit’s vision reveals its full power: documentary without voyeurism, poetic without artifice.

Through this image, the artist preserves a memory on the verge of extinction. A nomadic, Paleolithic way of life slowly erased by colonization, industrialization, and forced assimilation. In 1966, this scene still belonged to the present. Today, it is already history.

The Series: The Gubabingus, Australia

The Gubabingus arrived on the Australian continent around 40,000 years ago, likely with their dogs—the famous dingoes—during the prehistoric era, when Australia was still connected to New Guinea via the Cape York Peninsula. They are among the last known survivors of Lower Paleolithic culture, predating the Stone Age.

They practiced no agriculture or animal husbandry, living instead by hunting, fishing, and gathering. They had no dwellings or clothing, constantly moving through the desert from one water source to another. Each clan had sacred totems guarding their territory and waterholes.

Some of their customs included the abandonment of the elderly and, in the case of twins, the death of one infant to regulate population growth. Men and women lived separately. From the age of ten, boys were sent alone into the desert for two months to fend for themselves. If they returned, a ceremony would induct them into the community of hunters.

European settlers first arrived in Australia in 1770. What followed was a wave of massacres, and Western diseases decimated Aboriginal populations. From 1909 to 1969, the “White Australia” policy allowed for the forced removal of Aboriginal children of mixed descent to be raised in institutions and assimilated into white society.

Up until the 1930s, thousands of Aboriginal people were interned and relocated to reserves run by white authorities. Sport, entertainment, and the military were often the only ways for them to be accepted into broader Australian society. During World War II, many Aboriginal men joined the armed forces.

In the 1950s, a policy of assimilation was promoted, aiming for Aboriginal Australians to adopt a Western lifestyle. Since 1976, partial land restitution has been enacted. Many returned to the homelands of their ancestors, living in reserves known as “communities.” However, these groups today suffer from the effects of alcoholism and cultural loss. The way of life that Édith Lesprit photographed in 1966 no longer exists.

In 1770, Lieutenant James Cook wrote of the Aboriginal people:

"They are far happier than we Europeans... They live in tranquility, free from the inequalities of condition. The land and the sea supply them with all things necessary for life... They enjoy a pleasant climate and healthy air... They have no superfluity."

Biography:

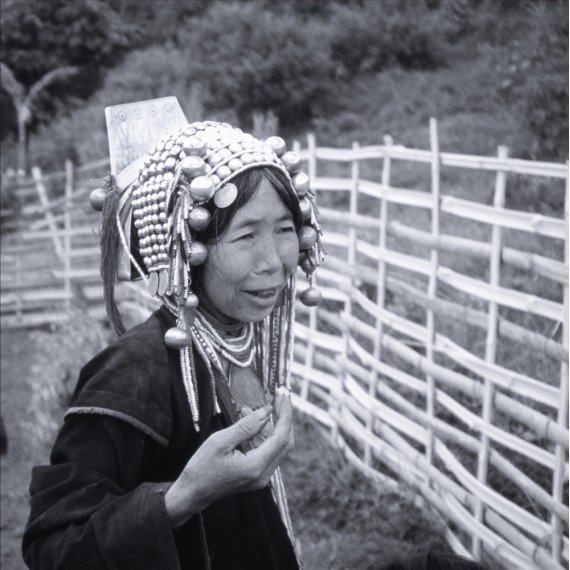

Édith France Lesprit was born in Paris in 1937. She studied ethnology in the United Kingdom. In 1964, she left Britain for Asia. In 1965, she encountered the Iban tribe, with whom she lived for several months—this experience became the subject of her thesis. She later lived among several other Asian tribes, from whom she brought back important documentary photographs.

In 1967, she met Mother Teresa for the first time in Calcutta. In 1975, she obtained a diploma in traditional Chinese medicine. From 1970 to 1980, she carried out humanitarian missions with Mother Teresa’s missionaries in the Charité hospices in Tejgaon, Bangladesh, and with the Salesian Sisters.

In 1976, she published Hell Where I Come From, a major testimony about Bangladesh, which received the Montyon Prize from the Académie française. In parallel, she wrote several novels for young readers, inspired by the tribes she encountered or her humanitarian work—some under the pseudonym Éric Lestier, others under her real name.

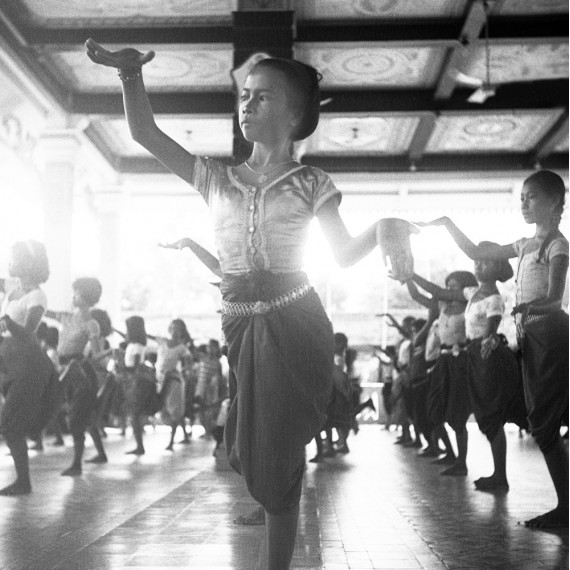

In 1978, she won the Grand Prize at the 7th Azur Biennial for a book on Chinese medicine. In the 1980s, she led many humanitarian missions in Cambodian and Laotian refugee camps in Thailand and was invited to speak on the subject internationally.

From 1990 to 2010, she trained "barefoot doctors" in Ethiopia—local nurses capable of providing basic healthcare. She also worked in leper colonies, rural clinics, orphanages, and homes for AIDS patients in Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. She has also supported projects for disabled animals near Bangkok.

In 2009, she published an autobiographical novel, The Kingdom of Forgotten Gods, recounting her journey with the Iban in Borneo.

Today, she continues her humanitarian work around the world, particularly through the development of a school for classical Khmer dance in Cambodia:

"My project is to build a school of classical Khmer dance for poor girls, while providing them with an education and the moral values specific to Khmer dancers. The goal is to give them a dignified profession that protects them from the grave dangers that threaten them (prostitution, human trafficking, forced labor), and to help Cambodia reconnect with its extraordinary past and civilization, as Khmer dance is an essential part of Cambodian culture."

Her photographs were exhibited for the first time in 2011 at Galerie Roussard, in the exhibition Tribes.